The Italian Communication Revolution

- Published on

- Author

- 魏彣芯

By Dr. Jason Yi-Bing Lin

What impact might history have witnessed if the Italian military genius Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) had encountered the inventor Antonio Meucci (1808–1889)? The possibilities are limitless.

In July 1850, Garibaldi arrived in New York as an Italian exile, seeking refuge with fellow Italians. There, he met inventor Meucci, who invited him to work at his candle factory on Staten Island.

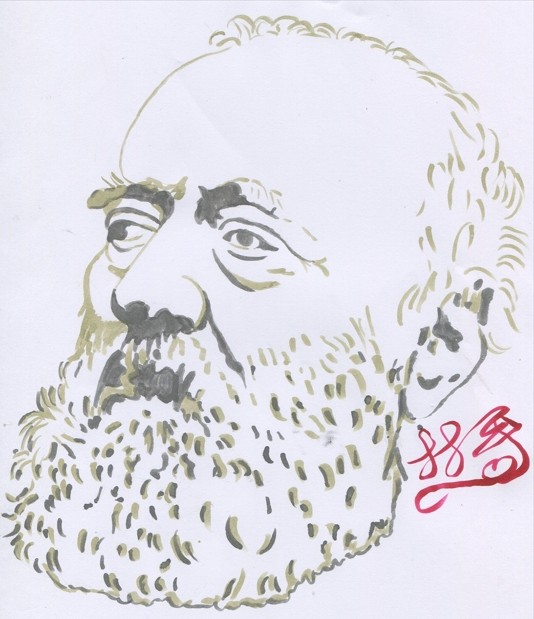

Hand-drawn portraits of Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) by Jason Yi-Bing Lin.

Garibaldi and Meucci developed a strong friendship. Meucci was working on an innovative communication device that would later be known as the telephone. One quiet evening, he demonstrated this technology to Garibaldi, who was impressed by its potential. Garibaldi immediately recognized how it could be utilized in warfare. Meucci then explained how to set up the telephone quickly, prompting Garibaldi to brainstorm ways to use it for communication during wartime.

At Garibaldi's urging, Meucci conducted experiments and made improvements to telephone technology at his candle factory. This endeavor was not only a technological challenge but also a race against time. Within a few months, Meucci successfully enhanced the telephone's performance, adapting it for use on the battlefield. Garibaldi then carried out a series of tests to ensure that the new communication method was stable and reliable enough for wartime conditions.

In April 1859, Garibaldi returned to Italy just as the Austrians declared war on the Kingdom of Sardinia. He rallied the 'Cacciatori,' a volunteer army, to resist the Austrian forces and integrated Meucci's telephone technology into his command system, quickly demonstrating its advantages. With the telephone, he could issue orders swiftly, adapt to the rapidly changing battlefield, and transmit intelligence between his troops in real-time.

On May 10, the Austrians began their retreat toward Lombardy. The telephone alert quickly informed Garibaldi, enabling his Cacciatori volunteer army to reposition and follow closely behind. This strategy exerted tremendous pressure on the Austrians, forcing them to stretch their forces thin to address potential uprisings in the Lombard towns. On May 27, after scouts reported enemy movements via telephone, the volunteer army engaged the Austrian troops at San Fermo and achieved a decisive victory. Following this success, Garibaldi entered Lombardy on May 27 and announced its annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Hand-drawn portraits of Antonio Meucci (1808–1889) by Jason Yi-Bing Lin.

The battle showcased the bravery and effectiveness of Garibaldi's volunteers. His army quickly achieved a series of victories due to their strong organization and coordination. Their telephone network was crucial in connecting the command center with various units and establishing flexible communication links across different battlefields. This laid the groundwork for the future Italian unification movement, known as the Risorgimento. During this time, Meucci maintained contact with Garibaldi, providing him with valuable insights into communication technology.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Giuseppe Garibaldi volunteered to serve under President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865). On July 17, 1861, he was appointed as a major general in the Union Army. Garibaldi advised Lincoln on how to utilize telephone communication to direct Union forces via telegraph, which became a crucial component in the war's outcome. Through Garibaldi’s innovative use of this technology, Antonio Meucci’s communication inventions gained recognition as legendary military advancements. These innovations not only changed the dynamics of warfare but also had a lasting impact on communication in the years that followed.